Cordye Hall: Dallas Peace Activist

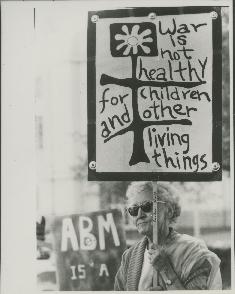

Cordye Hall protests the Vietnam War.

The sign she holds reads "War is not

healthy for children and other living things."

Allyson Hibdon

Cordye Hall, formally known as Cordye McLaurine, was born to parents Albert Lawrence McLauriene and Myrtle McCamant around May 31, 1898, in Jones County, Texas. Her exact birthdate is not known due to missing birth certificates. Hall was the youngest of six, although her older sister passed away before she was born; her remaining siblings were boys. She described her childhood as “spoiled” and “protected” by her older brothers, especially after her father’s death when she was around four or five years old.

Hall recorded stories of her childhood in an oral history, preserved in the Texas Woman’s University archives and in the Dallas Public Library. She also preserved her stories in a sixty-eight-page autobiography, What Can One Person Do?: A Texas Woman Activist Answers. She states that she was “one of them,” referring to her brothers, which in today’s terms, would translate to “one of the boys.” They did not indulge in toys, but she enjoyed walks, riding her Mustang pony, and roughhousing. At thirteen, Hall began work as a bookkeeper. She attended school in Merkel, Texas around 1910 where she stated that she was an “excellent student” but perhaps a bit of a handful. Shortly after 1910, she moved to Corpus Christi, Texas to follow her mother and one of her brothers, Albert, until her mother passed away from cancer in 1913. From that point on, Albert became her guardian and took her back to Dallas to stay with him, where she then graduated from Ursuline Academy in 1918 and married Oren Franklin Hall.

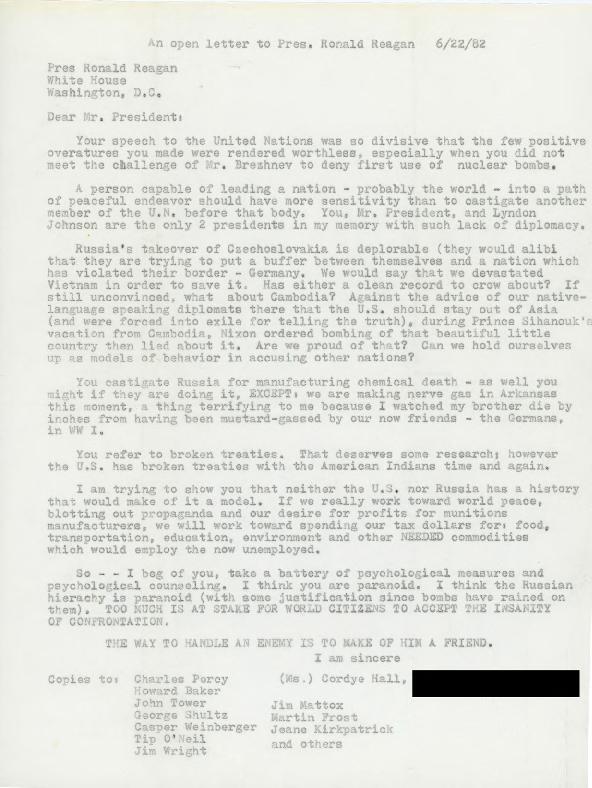

Letter from Cordye Hall to Preseident Ronald Reagan, 06-22-1982. The letter epitomizes Hall's direct questioning of political officials and business leaders in her political activism.

Following her graduation from Ursuline Academy, Hall worked as a bookkeeper and office manager off and on for sixty years. However, she is mostly remembered for political activism. She was very much involved in the peace movement, campaigning against global conflict and promoting integration. Her interest in the peace movement began after her own two sons, Wallace and Richard, fought in World War II. She marched with Vietnam protestors well into her seventies and wrote letters to big business corporations, politicians, and editors urging them to stop participating in harmful warfare. Hall eventually passed away in 1994, and was referred to as the “mother of the peace movement in Dallas”. Her legacy lives on through the Dallas Public Library, Texas Woman’s University archives, and her autobiography, What Can One Person Do? A Texas Woman Activist Answers.

I chose to utilize the ideologies presented in “Critical Feminism in the Archives” because Cordye Hall represents a powerful, system-changing, anti-war hero in Dallas, Texas. She took initiative in being the change she wanted to see in the world and fought to make not just Dallas, Texas, but America a war-free and safe space for all. She used her voice through her letter writing to address politicians and big businesses head-on, calling them out on their inconsistencies and challenging their rhetoric. I wanted to use this subcollection to exhibit her grit, perseverance, and the importance of exercising First Amendment rights.

Ms. Cordye Hall was more than a peace activist. She was an example for people everywhere. She challenged systems put into place that she thought to be dangerous for her fellow American people and she cared about the futures of the children that would be affected by war. Her no-nonsense letters prove that she was not afraid to ask hard questions, and demand answers. My goal through Hall’s subcollection is to showcase her political activism prowess and inspire others to embrace their inner peace activist and choose to make a difference wherever they are, no matter how big or small. It is not to fill in any gaps or take control of her story, but to display her letters and photos in a respectful manner that honors her legacy.

Works Cited

Cifor Marika, and Stacy Wood. “Critical Feminism in the Archives.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.27.

Hall, Cordye. "What Can One Person Do?: A Texas Woman Activist Answers. 1988. Print.