Introduction

Nicole Chinn, Elizabeth Headrick, Allyson Hibdon, Alexis Kaftajian, Kate Mueller, Shannon Quist, Daniel Stefanelli, Emily Ramser, Bethany Weston

At the beginning of the spring 2019 semester, our Bibliography and Research Methods graduate class dove into TWU's Woman’s Collection in search of writings by women to highlight and digitize. As we explored the archives, we excavated texts and photos within the different collections; we found ourselves repeatedly drawn to the personal writings of a select group of women, specifically their letters. Using these personal documents, Moments of Inscription reconstructs forgotten narratives, evoking the original contexts of their authors and subjects. Left unmined and unconsidered by the casual observer, these materials lacked the spotlight needed to draw the audience they deserved. This collection aims not only to celebrate these materials as examples of personal communication but also to present them as storytelling elements that cement their authors' identities, self worth, and narrative presence.

Digitization played an essential role in the curation and creation of Moments of Inscription. Rather than taking for granted the ease with which we were able to access and preserve the collections and documents, we purposefully considered questions of audience and purpose while weaving the many elements of this collection together. Determining that a digital platform would provide the widest reach for the completed collection, the curators of Moments of Inscription scanned numerous documents and have carefully considered the structure of the collection as a digital artifact and extension of the university’s archival spaces.

In the introduction that follows, we address the historical context that drew these women together, the function of letter writing as a genre, and the methodology that drove our decisions as curators. For example, we address the wide variety of women’s lives that we surveyed by organizing them into three broad categories that correspond to the brunt of their lives’ work: military service, education, and activism. Considering these categories allows us to address the function of these personal writings, in both personal and public spheres, and situate the duality of those functions within the broader history of letter writing. We close with our methodology and rationale for selecting a genre with untapped potential. The resulting collection seeks to draw you deeper into the lives of these women and their legacies.

Letter from Dorothy Scott to her mother, February 24, 1943

Letter from Harry Kelso to Rema Lou Brown

Personal forms of writing, namely letters and correspondence, are the focal point of Moments of Inscription because they offer insight into women’s lives through their own words. In the digital age, personal writing still exists as a genre that is rife with untapped potential. Its form has evolved, yet it persists in our daily lives as motivational notes on bathroom mirrors, texts to a beloved friend, and emails to coworkers. For instance, within Moments of Inscription, we have presented the personal letters of Dorothy Scott and Margaret McCormick, sent home from the thrills of flight; persuasive letters like those from Dr. Edra Bogle, sent in hopes of change; and letters to friends far beyond reach, like Francis Mulkey Keys’s penpal. Personal writing became the genre of choice for this collection because these women chose it as theirs.

Often excluded from sharing their opinions in traditional public fora, women have historically turned to letter writing not only as a practical mode of communication but also to amplify their voices. Concentrating on the 20th century, the writings assembled for Moments of Inscription celebrate women who negotiated their roles in public and private spheres, arguing for equal status in the eyes of the law and society. They exhibit women’s varied roles as educators, activists, soldiers, and writers and attest to their personal relationships as mothers, daughters, wives, friends, and lovers. In every letter, journal entry, and note, they recorded the events of their lives on their own terms and in their own words. Whether these letters were handwritten to friends or typed to professional colleagues, they showcase the multiplicity of women’s voices through their diverse life experiences. For instance, some of these letters are to family members or friends, proof of close relationships. Others are professionally typed and sealed in what once were crisp envelopes, proof that women were actively engaging in the public sphere. For instance, the papers of Rema Lou Brown, a Houston-area feminist, documents her very public involvement in a number of political causes. We have also uncovered materials that demonstrate dedications to worthy causes, frustrations of daily life, and works of art that sat in the spotlight for only a moment. Once such gem is Caro Brown, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist whose story and struggles are now largely unknown.

As with every human being, the lives of the women featured in this collection are vast, and multi-layered. In truth, the portrait we have created is merely a glimpse into a complex and diverse group of women, encompassing a broad spectrum of personal and professional choices, from journalists and World War II Air Force pilots to educators and community organizers. Their stories are powerfully unique but also speak of one essential commonality: in the face of discrimination, social expectations, and challenges, they made their own choices about their lives.

Specifically, in the field of activism, the women featured in our collection assumed many different roles and responsibilities as they advocated for gender equality, political involvement, and LGBTQIA+ rights. Each of the women featured in Moments of Inscription fought for what they believed in in order to effect social change. For example, Caro Brown, a Texas native, is the only female journalist from Texas to win a Pulitzer prize for local reporting, for her coverage of the corrupt political systems in Duval County, Texas for the Alice Daily Echo. However, due to the wage gap in journalism, after receiving the Pulitzer, Brown never wrote for a public audience again despite constant advocacy for herself and other female journalists. Dallas peace activist Cordye Hall was a determined woman who wrote open letters to politicians, such as presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Ronald Reagan, and big businesses, such as General Motors, urging them to cease their participation and affiliation with nuclear warfare. She organized protests and was known around Dallas, Texas as a “Mother for Peace.” Toward the end of her life, she wrote an autobiography, entitled What Can One Person Do? A Texas Woman Activist Answers, in which she encouraged other women to get involved in local politics, another prominent feature of her letters. Rema Lou Brown, who lived in the Houston area, was active in her community in the 1970s and 1980s. She was a counselor and coordinator for Women’s Resource Services at the University of Houston at Clear Lake City and a member of the American Association of University Women (AAUW). Brown was also an organizer for many women’s groups, and was the driving force behind the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston. An equally fierce advocate for equality, Dr. Edra Bogle fought for LGBTQIA+ rights through her letter writing. She utilized the genre to tackle discrimination against queer folx in the Dallas-Fort Worth area and across the nation. She often wrote on behalf of LGBTQIA+ organizations in and around North Texas, providing a voice for underrepresented minority groups. Despite their differences, these women are united in their tireless fight for change.

Postcard from Dorothy Scott to her sister-in-law, March 9, 1943.

Card to Jeanann Madden from student Michelle Jones

Moments of Inscription also features three women who served in the United States military. While each woman's experience was different, they are connected in their sacrifice. All three of these women offered differing perspectives on female military service while allowing insight into their personal lives. Dorothy F. Scott, a pilot and adventurer, made the greatest sacrifice of all for her nation, when she was killed during service in 1943—a life unfinished. A member of the WAFS or Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron during World War II, Scott’s letters to her family share stories about the new places and people that she encountered through her travels. She also wrote about her experiences as a female pilot in the Air Force. Like Scott, Margaret E. McCormick devoted her life to military service and was a member of WASP class 43-1, also known as “The Guinea Pigs” because they were the first participants in the program. McCormick served during World War II and struggled to adjust to civilian life. Postwar, she worked as an air traffic controller for the armed forces. Her papers include letters to her close friend and fellow World War II veteran, John Mayhead. In these correspondences, McCormick discussed her daily life and troubles, while offering comfort to Mayhead when he became a prisoner of war in Germany. Scott's and McCormick's service paved the way for women like Jeanann Madden, who served in the later twentieth century during the Gulf War. An eductaor and army reservist, Madden sent her beautiful handwritten letters primarily to her mother and close friends, detailing her day-to-day experiences in the army and civilian life. While completing her service in the army, she received many letters from her students thanking her for her service to her country. These three different women mirror one another in courage, bravery, and adventure.

Of course, none of our categories—activist, soldier, educator—is necessarily mutually exclusive of the others, as Madden's life as an educator and soldier attests. Two other women in our exhibit devoted their lives to educating others. Frances Mulkey Keys was an elementary school teacher, wife, and daughter who lived in Texas all 76 years of her life. Keys valued familial history and had an interest in global friendship, as her thirty-year correspondence with her Finnish penpal demonstrates. She wrote about her daily life in her correspondence and continued to maintain her professional and personal focus on education. While Keys taught elementary, Edna Ingles Fritz joined the faculty of Texas Woman’s University in 1917, then known as the College for Industrial Arts. Fritz Fritz taught in the Textiles and Clothing department, eventually accepting the role of department head. During her tenure as professor, her progressive beliefs and ideas led to her involvement in founding the Denton chapter of the American Association of University Women in 1928. Fritz also used her knowledge of materials and design to advocate for the health and wellness of women, infants, and children. Both of these women’s letters show their passion for education as well as community issues.

Each letter, photo, and document is a snapshot, an instant of stasis, in an otherwise dynamic, evolving portrait. Therefore, we caution that Moments of Inscription cannot paint and frame a wholistic depiction of each woman. This collection tells these women’s stories as fully as the materials allow. It reconstructs historical context as completely as possible while leaving windows of missing narrative open for you to look through and view as you will. These artifacts, as the curators and audience approach them now, are permanently out of context: their journeys affected by an enormous number of factors. Perhaps these letters once sat on tabletops or in baskets. Some of the documents we have stumbled upon might have been sloppily filed away in cabinets, diligently pored over in coffee shops, or covertly tucked into messy desks. However, no matter how complex the journey, the entirety of a person’s life is not wholly contained by material objects but rather crystallized through the materials they have left behind. Moments of Inscription is a place to begin. We invite our audience to consider the written past of these women not as a static or finite narrative but instead as a web of stories influenced by its original context while remaining open to individual interpretation.

Letter Writing: Our Genre of Choice

The act of letter writing is not revolutionary in the twenty-first century even if it is now viewed as eccentric and old fashioned. This view of letters likely stems from the reality that “so much of our communication today is very compressed and immediate” (WBUR). Therefore, any mode of communication that does not result in a quick response is now viewed as outdated. Today’s readers—living in an age of smartphones, quickly typed emails, and the ubiquitous text message—should recall that letters and personal writings embodied diverse forms and served multiple rhetorical functions throughout history. The advent of new technology has not erased the importance of letter writing in our cultural history, even if it has obscured it, as it concerns both history and Moments of Inscription.

Indeed, letters were not always intended as private documents and were often intended as vehicles for public discourse. History is, in fact, littered with influential open letters such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Furthermore, letters are the backbone of the epistolary novel, a text comprised of mostly letters following a narrative, a form popularized in the eighteenth century. This genre was, and still is, immensely popular among women writers as it was a textual form that they were familiar with. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is, for example, one of the most prominent epistolary novels. Throughout the work, Shelley uses letters as framing devices, shifting the focus to include multiple narrators. Just as letters would have factored centrally into Shelley’s life in the nineteenth century, letters play a key role in one of her most celebrated literary works.

Letter writing has functioned as an enduring mode of communication through history. Since the 11th century, people have utilized letter writing as a “versatile form for a wide range of uses: personal, intellectual, administrative, diplomatic, commercial, and artistic” (Shemek 1). Whether desiring to stay in touch with a distant friend or composing an open letter that functions as a political statement, letter writing continues to carry weight not only as communication but also as a genre.

While the original intent of the letter writer can dictate the document’s function, the recipient of each piece of correspondence also plays a role in determining the purpose. Much like writing a novel, writing letters requires the author to consider questions of audience which could potentially change the content and tone of what they write. For example, while the content of two letters may both be a retelling of an important even by the writer, they may be written differently to appeal to different readers.

Identifying the specific functions performed by the letters in our collection is essential in order to locate their shared spaces. Consideration of these spaces affords further understanding of the women's lives whose artifacts we collect here. Multiple features of each letter informed the curators' selection processes: the content of each letter; the material method of communication, be it handwritten letter, typed document, or telegraph; and, finally, the letter’s current place within the archives. This body of information invites us to explore the dual functions shared by many of these letters. First, we will look at the primary function of each letter as an original message transmitted to a specific audience. Then, we will examine the secondary, yet equally important, function each letter currently serves within the archive as a material reference point, connecting the Woman’s Collection to the broader historical narrative of women’s rhetoric within personal letter writing.

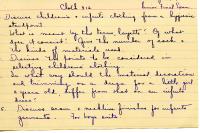

Clothing 312 Senior final exam note written by Edna Fritz, ca. 1921

Letter from Sukie White at NASA to Rema Lou Brown

The women whose correspondence we have curated for this digital collection used their personal communication across time and space as a means to connect with a wide variety of public and private audiences in order effect change and to constantly reorient their inner selves with the outside world. It follows that our digital collection reveals a panoramic scope of function. For example, Fritz filled many index cards and repurposed scraps of paper with precise cursive notes. These notes—written for her own use—cover the course curriculum she created, gather citations to support this curriculum, and provide visual aids when words did not suffice. In this instance, the function of Fritz’s personal writing was to crystalize what she wished to communicate to her students as she facilitated their personal growth. Rema Lou Brown’s letters, which contains a great variety of professional correspondence, reveal a very different function. For example, a letter from Sukie White at NASA Houston regarding a new women’s week program on which the two women were collaborating facilitiates the women's ability to conduct business and planning long distance. As these two examples demonstrate, when addressing primary function we find it helpful to split the letters into two subcategories based on each letter’s audience: professional, which we term public-facing, and personal, which we’ll refer to as private-facing.

Letter from Cordye Hall to D.C. Burnham, July 22, 1970

Letter from Dorothy Scott to her father, September 8, 1943

A great many of the public-facing letters in this collection document decades of activism dedicated to the interconnected areas of women’s issues, LGBTQIA+ rights, and environmental concerns. The primary function of such letters was to effect meaningful change catalyzed by the power of words. Hall’s subcollection, for example, reveals that her activism occured at the intersection of humanism and environmentalism where she used letters as politically charged polemics protesting nuclear weapons for their effect on both society and the planet. These public-facing letters addressed, first, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and then President Ronald Reagan. Beyond the presidents, Hall’s intended audience for these open letters was the whole of our nation. Her potent words functioned as a blinking neon arrow focusing America’s eyes on the devastation wrought by nuclear warfare.

In contrast to the broad audience and large-scale function of Hall’s letters, the personal-facing letters have a sense of intimacy, communicated through inside jokes, quiet frustrations, and secret celebrations. For example, in one exchange of letters, Scott and her father discuss how she will pay taxes for a job so new it did not yet have a tax protocol. While such private-facing letters may seem trivial, their function was important. Taken together, Scott’s letters functioned to maintain her close familial relationships. They also provided a safe space where she could vent about the difficulties of being a woman in the military. When distance denies a physical safe space between two people, private-facing letters may serve as Scott’s and open up a mental safe space.

The letters and personal writings in Moments of Inscription each function as invaluable contributions to the history of women’s rhetoric as a result of their archival presence, embodying their second function as historical artifacts. By thoughtfully collecting, curating, and engaging with these writings, there exists a collaborative effort to knit these narratives into the gaps and holes of the greater history of rhetoric. Because the extant documentation of the history of rhetoric does not spare much attention to women, it is necessary to “think differently about where and how to look for women’s contributions” (164), as noted by Brenda Glascott, Assistant Professor and Composition Coordinator at CSU of San Bernardino. Glascott’s scholarship focuses on marginalized genres of writing like those highlighted in this collection. She points to the recovery work done by feminist historiographers as validation that different source materials and methodologies locate women’s rhetorical legacy in peripheral places like conduct guides, diaries, and letters. The letters curated in this collection, and the narratives they write, are part of this recovery work. As you explore the writings and ephemera in each subcollection, you also become part of this work. Your engagement helps to unveil women within the history of rhetoric.

Methodology

As archivists, we viewed these letters as extensions of their writers’ physical bodies and the spaces they occupied throughout their lives. Doing so encouraged purposeful selection and arrangment of letters into various subcollections in order to create a meaningful narrative. Our archival decisions pulled from the feminist historiography methodology that focuses on exposing and addressing blind spots in archival methodology through critical and intersectional feminist theory as proposed by Marika Cifor, Assistant Professor at Indiana University, and Stacey Wood, Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Modeling their practices, we attempted to conduct our work while being “self-consciously engaged in a kind of history making about history makers who conceived of their interventions as vital correctives to standard historical practices” (Cifor & Wood 3).

Furthermore, our methodology is also dependent upon the idea that “[a]rchival records and collections reflect processes of living,” in accordance with the viewpoint centralized in the work of Jamie Ann Lee, Assistant Professor at University of Arizona (19). Through this framework, we created Moments of Inscription as a collaborative, community-created digital archive. Cifor and Wood remark that community archives have “tremendous potential” when they are created purposefully, but that they also have the potential to “reproduce hierarchies and exclusions through their processes and interpretations of records and collections that reify damaging and unjust social structures” (21). As we have no desire to reproduce such conditions, we followed Lee’s “Queer/ed Archival Methodology” by resisting “an urge to stabilize these records into skillfully accessible collections in order to consider new ways to understand and represent such dynamic bodies that produce records and are produced by records” (5).

In order to create this space, we approached the creation of Moments of Inscription not by looking for one specific kind of letter or woman, but by allowing the collections themselves to guide us. We looked through each box and file, giving space for the women to tell us their stories and indicate what was important to them through what they chose to write about and save. Some of the women in this collection preserved handwritten notes, like the hand-drawn cards Madden received from her students while overseas. While others, like Rema Lou Brown, kept meticulous meeting notes from the organizations they were involved in. We allowed their materials to shape our archival choices.

Yet in doing so, we found ourselves left with incomplete narratives. The women’s individual collections were formed from what they had chosen to save during their lifetimes or by what family members or friends decided to give to TWU’s Woman’s Collection. We found some collections, Caro Brown’s for example, that did not include many letters written by these women but rather to these women; however, these writings were still important to the reconstruction of narrative and context. Additionally, gaps were intentionally introduced to protect sensitive information and observe copyright. To artificially fill these gaps in order to create a clean and whole narrative would have been doing a disservice to these women's stories. As such, we made the decision to allow unfinished stories to remain as they are within our collection.

In closing, we acknowledge that the narratives we interpret from these letters might be different from what you interpret. Regardless of your purpose, we invite you to peruse these letters and engage with the private and public lives of these women in order to share their stories. We also invite you to help these women’s stories continue to grow and shift by adding to this digital archive through your own interpretations and additions.

Works Cited

“A Case For The Dwindling Art Of Letter Writing In The 21st Century.” WBUR, 5 June 2004, www.wbur.org/radioboston/2014/06/05/letter-writing-century. Accessed 10 Apr. 2019.

Cifor, Marika, and Stacy Wood. “Critical Feminism in the Archives.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.27.

Glascott, Brenda. “Revising Letters and Reclaiming Space: The Case for Expanding the Search for Nineteenth Century Women’s Letter-Writing Rhetoric into Imaginative Literature.” College English, vol. 78, no. 2, National Council of English Teachers, 2015, pp. 162-182. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44075105. Accessed 22 March 2019.

Lee, Jamie Ann. “A Queer/ed Archival Methodology: Archival Bodies as Nomadic Subjects.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017. doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.26.

Shemek, Deanna. “Letter Writing and Epistolary Culture.” Oxford Bibliographies, 19 Mar. 2013, www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0194.xml. Accessed 10 Apr. 2019.