Rema Lou Brown: Feminist, Activist, and Educator

Elizabeth Headrick

Rema Lou Brown is a history maker. The story that her ephemera tells is that of a community leader and organizer with deep convictions and a belief that women should hold an equal place in society. Throughout her work as a feminist activist she struggled against those who held very different opinions, a fact which is immediately evident in materials from her archive, including a handwritten, eight-page document that recounts her experiences with anti-feminist protestors at the National Women’s Conference in 1977. From organizing and running the National Women’s Conference to her activities on the University of Houston-Clear Lake Campus, she worked to ensure that equal rights were available to all individuals. Thus her absence from the larger story of second-wave feminism in Texas and America is surprising. Marika Cifor and Stacy Wood discuss this kind of archival lacuna in “Critical Feminism in the Archives”. Cifor and Wood place an emphasis on the history of history makers like Brown, and the ways that these history makers attempted to make “vital correctives to standard historical practices” (Cifor and Wood 3). The absence of Brown and others like her need to be corrected. History makers like Brown should be considered key figures of second-wave feminism and yet we know so little about her. The documents that I have chosen to highlight for this collection--including letters, newspaper clippings, and personal notes-- are intended to give a more full and well-rounded picture of who this history maker was as a feminist, reproductive rights activist, and community leader.

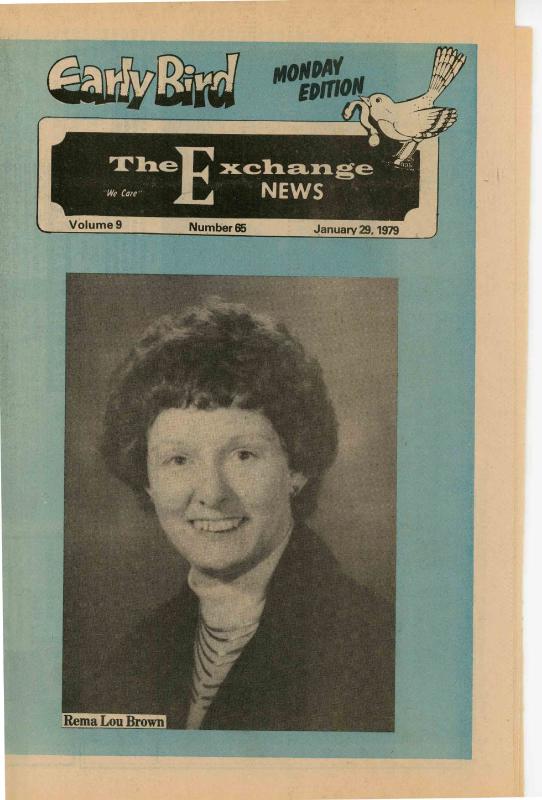

Even after extensive research, the specific circumstances of Rema Lou Brown’s birth and early life are unknown to me. A Houston-area newspaper article from 1979 tells the reader that Brown graduated from high school in Kansas City, Kansas in 1953. After high school, she attended Parsons College in Iowa where she played basketball, was a cheerleader, and was a member of the Alpha Gamma Delta sorority. These pursuits served as an early indication of the level of activity that Brown would maintain throughout her life. After completing graduate work at Rice University and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Brown settled into her final graduate work at the University of Houston-Clear Lake Campus (UH-CLC) in the 1970s where she made a life with her husband and two sons.

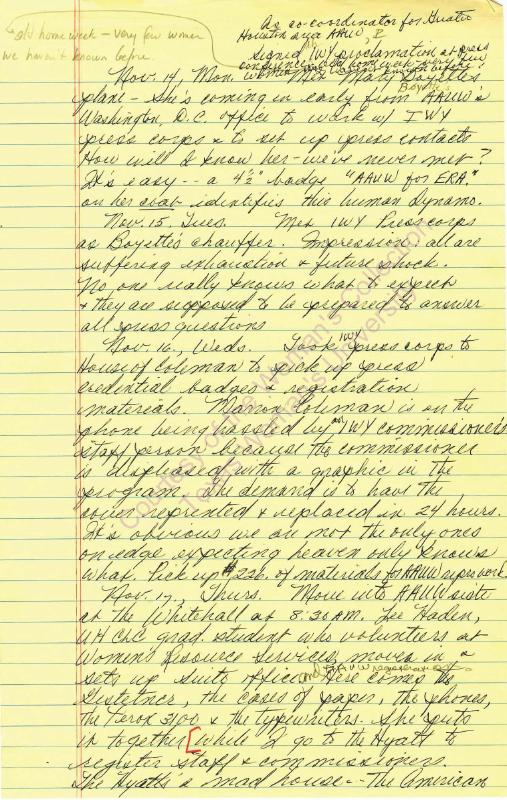

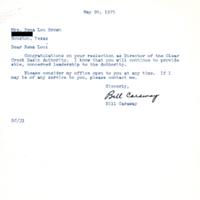

While we do not know the exact nature of Brown’s graduate work, her collected papers indicate a heavy interest in Women’s Studies, which was still in the early stages as an academic discipline in the 1970s. It was during the course of her graduate work at UH-CLC that Brown worked as a counselor and coordinator at the Women’s Resource Services, located on campus. Brown appears to have become involved with the Houston-area feminist community while she was working at UH-CLC. Not only did she work to promote the concept of rape culture in the early 1970s academic community, but she also helped to start and run Houston Area Federal Feminist Credit Union--the first feminist credit union in Houston--and she coordinated and oversaw the National Women’s Conference that took place in Houston in November 1977. Brown was also a devoted advocate for Planned Parenthood which is evident from the speeches, programs, and flyers that were collected in her archive. Many of the events referenced in these particular materials included Brown as either a coordinator, speaker, or attendee. To her credit, Brown believed in and supported many causes and worked on numerous committees, even serving as the director of the Clear Lake Water Authority Board. Letters contained in the archive, and highlighted within this collection show that she was valued in this position and served her community well. She is praised particularly for her ability to defuse a rather tense and dramatic situation that occurred with the board during her tenure as director.

All of the letters, handwritten notes, newspaper articles, and clippings that I have chosen to display in this collection comprise only the smallest portion of Brown’s large and active life. She strikes the reader as a capable and competent woman and the letters that were sent to her reveal that she was well-liked and respected. Despite the praise and respect, despite all that she did, Brown would insist that she was not a “Superwoman,” in the same 1979 article that gave us some of the few tantalizing details that we have about her life and who she was. Brown instead credited the support of her husband, her sons, and her friends for allowing her to be so involved in her community.

Brown was a woman who was very much of her time in her feminist activism, but she was also a woman ahead of her time. While most of the material could not be placed in this digital collection due to time constraints, her archives reveal a wealth of information regarding not only women’s rights but also civil rights for everyone, no matter the race, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Brown kept everything that came across her desk that she felt might be of use at a later date, including programs for art exhibits, schedules and syllabi for Women’s Studies programs at other colleges and universities, and newspaper and magazine articles that had any connection to the women’s movement in America. Altogether, the collection that I have created, while small, displays the story of a true history maker, but one that is not known in a larger sense, and I believe that it should be known.

Works Cited

Cifor, Marika, and Stacy Wood. “Critical Feminism in the Archives.” Journal of Critical Library

and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.27.