Edra Bogle: North Texas 1970s LGBTQ+ Trailblazer

In a performed oral history through The Outrageous Oral program, Denton LGBTQIA+1 activist and scholar Edra Bogle recounted her coming outs: “I have come out five different ways five different times” (Bogle, Outrageous Oral). Yet, as I write this introduction, I keep finding myself thinking of this collection as Bogle’s sixth coming out; within the letters collected here, she outs herself time and time again as queer.

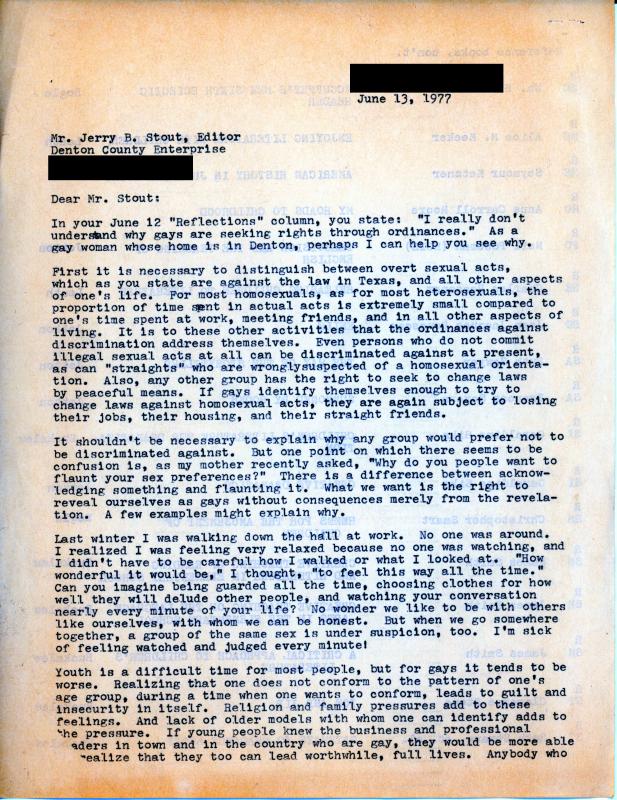

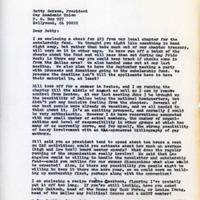

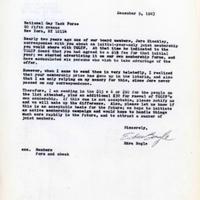

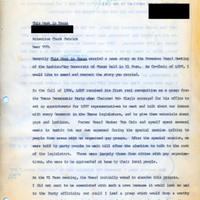

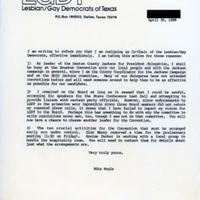

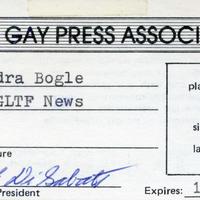

For example, in a 1977 letter to the Editor of Denton County Enterprise Jerry B. Stout, which is showcased in this subcollection, Bogle describes herself as a “gay woman whose home is in Denton” (Bogle, Jerry B. Stout). As she told Stout in that same letter, she was often afraid to out herself “lest my friends and my employer be upset and indeed ostracized” (Bogle, Jerry B. Stout). She also, however, outs herself as a woman, as a scholar, and as a political activist in her writings and details the discrimination she experiences in these intersectional identities. As one of the first queer college faculty members to come out in Texas2 she felt she was “watched and judged every minute” (Bogle, Jerry B. Stout).

In donating this collection, Bogle gives implicit permission for this coming out, yet as the archivist processing and digitizing it, I do not want to take control of it from her. Doing so would only reinforce the discrimination and fear she discussed in her letter with Stout. Instead, I would prefer Bogle’s letters guide researchers with minimal archival influence. It is impossible for me to remove my influence completely, as I have selected both what has been digitized and not, yet I employed the Queer/ed Archival Methodology in working with this collection in order to attempt to maintain Bogle’s agency and autonomy as a queer woman in this telling of her story.

Doing so required me to view each piece of Bogle’s physical collection as not just a static historical artifact but rather as a piece of an ongoing story. Ideally in a collection that utilizes this methodology, everything would be digitized; however, due to time and labor constraints, I instead had to selectively choose a portion of Bogle’s files that I felt best told her story, and best facilitated her coming out.

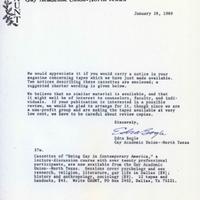

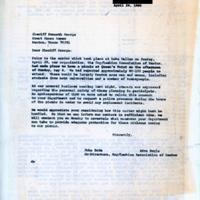

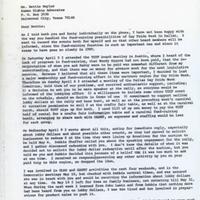

When I first began digitizing this collection, it was unprocessed, which means the collection’s boxes had no order beyond that created by Bogle at the time of donation. Canceled checks, torn envelopes, and stickers existed alongside letters, meeting notes, and project drafts. Yet the chaos of the collection was not just a result of unprocessing; it is the product of the time period in which Bogle lived and worked as a queer individual during the AIDS crisis. Those she worked with were dying, and when they passed, their projects often did as well. The queer community at this time was one of fluctuation.

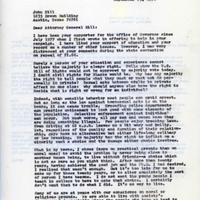

This state of flux made it difficult to choose letters, as many pieces of the stories here are missing. In her letters, Bogle frequently discusses projects that may or may not have come to fruition and responds to lost inquiries and conversations. There is no record of many of the things she writes about beyond her letters. These gaps, however, are important, as they demonstrate not only what it was like for queer folx at the time, living in a state of constant uncertainty due to AIDs and anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation in the 1970s and 80s, but they also provide a personal context for Bogle’s life. For instance, in a 1983 letter to Louis Crew, Bogle discusses what it was like to have to deal with the FBI surveillance of queer groups at the time and how she and others had to fight against the recriminalization of sodomy in Texas. As such, in creating this collection, I made the decision to digitize letters that highlighted Bogle’s life and work in addition to letters that show what it was like to be queer at this time, as I felt letters that explored that provide a backdrop and historical context for Bogle’s archival coming out.

According to the Queer/ed Archival Methodology, “[a]rchival records and collections reflect processes of living” (Lee 19). It is my hope that this collection reflects Bogle’s processes of living and that it enables her story to keep being told and keep growing.

Endnotes

1 In keeping with the Queer/ed Methodology, I wanted to be aware of the living nature of the archives. I chose to model this in the language I use both here in the introduction and in the metadata. Specifically, I made the choice to use three words: LGBTQIA+, queer, and folx. The first is an acronym that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and asexual. It is generally used as a catchall term for those who are not heterosexual and/or cisgender. Queer was once used as a slur against homosexual individuals; however, the community has begun to reclaim it and use it as an umbrella term similar to LGBTQIA+ (Zaltzman). I use them interchangeably as adjectives so as ensure its inclusivity since it discusses many folx whose sexual orientations are unknown to us and may never be known. Folx is another term used for inclusivity, as it is an “umbrella term for people with a non-normative sexual orientation or identity (Raedel). It primarily is used when talking about trans and non-binary folx, which is why I am using it here, as many of those discussed and included may be trans or nonbinary, and I wish for my language to be inclusive if so. Lee’s methodology calls for us to allow collections to grow and change, and I believe that utilizing this kind of language does so, as the queer community is known for finding words for identities that queer folx have always had but never had the words to name.

2 According to Pride Alliance at the University of North Texas, Bogle “Was one of the first three faculty members in the state to come out publicly, each in connection with academic activities” (“LGBT History”).

Works Cited

Bogle, Edra. “Outrageous Oral, Volume 18 UNT: Edra Bogle - Thursday, Oct. 15, 2015.”

Youtube, uploaded by The Dallas Way, 22 October 2015, youtu.be/297-9MgDQE. Accessed 10 April 2019.

---. Received by Jerry B. Stout, 13 July 1977.

“LGBT History in Denton.” Division of Institutional Equity & Diversity,

edo.unt.edu/lgbt-history-denton. Accessed 10 April 2019.

Lee, Jamie Ann. “A Queer/ed Archival Methodology: Archival Bodies as Nomadic Subjects.”

Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017. doi:10.24242/jclis.v1i2.26. Accessed 10 April 2019.

Raedle, Joe. Womyn, Wimmin, and Other Folx - The Boston Globe. The Boston Globe, 9 May 2017, www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2017/05/09/womyn-wimmin-and-other-folx/vjhPn82I TGgCCbE 12iNn1N/story.html. Accessed 10 April 2019.

Zaltzman, Helen. “Allusionist 79. Queer.” The Allusionist. 1 June 2018.

www.theallusionist.org/allusionist/queer. Accessed 10 April 2019.