Margaret McCormick: Patriotic Pilot

Daniel Stefanelli

Margaret E. McCormick was a graduate of the first class of WASP—Women’s Airforce Service Pilots. Technically a civilian program, the WASP were female pilots who served the war effort by testing and ferrying aircraft, the idea being that their service in these roles freed male pilots for use in combat. A skilled, competent pilot who had already logged more than 1100 hours of flight time in private aviation, McCormick was among those who volunteered to serve as the country reeled from the attacks on Pearl Harbor in 1942.

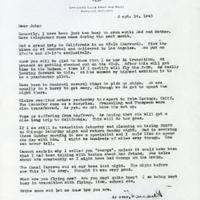

The papers assembled in this collection are some of her correspondence with her friend John W. Mayhead, who was at the time a sub-lieutenant in the Royal New Zealand Naval Volunteer Reserve. The earliest letters, dated just after her graduation from the training program, tell of her first experiences as a WASP—the grueling training, the media publicity, and the controversy over whether they were fit to wear military uniforms. After graduation, McCormick was assigned to the Ferrying Division of the Air Transport Command, shuttling aircraft across North America to ensure they were ready for use in combat. She writes of her many flights and the models of aircraft she flew on pages postmarked from field stations across the country. Writing to Mayhead, himself a military pilot, theirs is a conversation between equals: two pilots engaged in the service of their respective countries, allies in every sense of the word.

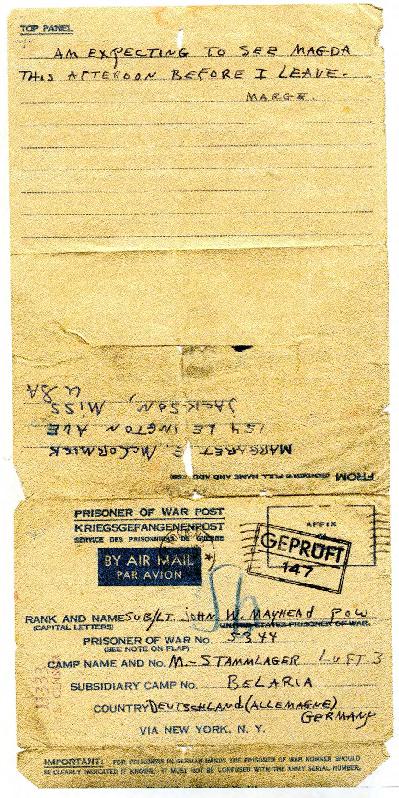

In 1944, Mayhead’s plane was shot down by anti-aircraft fire, and he was taken as a prisoner of war by German forces. McCormick’s letters to him from this period are addressed to Stalag Luft III prison camp in Germany—handwritten; the envelope stamped with the seal of the kriegsgefangenenpost, the postal service for prisoners of war held in Germany. In a very real way, the letters physically embody the drama and tragedy of the war. McCormick clearly attempted to maintain the usual light, convivial tone of their letters—a tone in jarring contrast with the reality of Mayhead’s situation. In a letter dated November 11, 1944, she writes about her new parka––“blue with a brown fur hood and lining”––and about the shows she had recently seen. She enjoins Mayhead to “keep [his] chin up,” but the words feel hollow and forced, belied even by the physical form of the letter itself, with the austere stamp of the German censor across the front of the envelope.

McCormick writes of the celebrations at the end of the war, but her return to post-war life was hardly a smooth one. McCormick was disenchanted by the disbandment of the WASP program in December of 1944, which––as she describes in a letter dated July 3, 1945––she viewed as an entirely political decision brought about by “draft-dodgers.” She drifted aimlessly across the country for months, first visiting her father in Jackson, Mississippi, before setting out for New York. At this point, she grew “tired of being idle” and of carrying a heavy conscience over “doing nothing to help bring [the] horrible war to a successful completion.” So McCormick joined the Women’s Army Corps, where she began life anew as a private, after achieving the rank of officer in the WASP. She eventually became a military air traffic controller––allowing her to maintain at least a small connection to the aviation world in which she belonged.

But after that, the archival record is silent.

Altogether, McCormick’s papers occupy one slim folder, tucked away in the depths of Blagg-Huey Library. While her letters give us valuable insight into her experiences as a WASP, very little has been recorded about her life before or after the war. Far from providing answers, her letters only raise more questions. What became of her after the war? How did she meet Mayhead? What was the exact nature of their relationship? These are questions that her letters alone cannot answer.

In curating this sub-collection, my goal has instead been to create an accessible collection for future scholars, WASP historians, or anyone curious about women’s contributions to WWII. In selecting materials for digitization, I have tried to choose a group of items that is representative of the collection as a whole, both thematically and with respect to the time span represented in the letters. Drawing on Jamie Ann Lee’s Queer/ed Archival Methodology, I have also given special attention to my role as archivist and storyteller, in my efforts to represent two different stories I saw unfolding in McCormick’s letters: a story of her relationship with Mayhead and, on a much larger scale, a story about an American experience of WWII.

With respect to the latter, I have relied on the principles laid out by Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook in their 2002 article “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” In it, the authors challenge the prevailing view of archives––and archivists––as neutral and objective. Instead, Schwartz and Cook explore the role of archives in shaping collective memory. Because WWII still looms so large in the American collective memory and, I would argue, in constructions of American self-image, I have paid heed to Schwartz and Cook’s insistence that “remembering (or re-creating) the past through historical research in archival records” is not a neutral retrieval of historical documents (3). Instead, the archives actively create a framework that shapes our understanding of the materials they contain. The materials I have selected therefore necessarily reflect my subjective understanding of WWII and those selections, in turn, will echo through the archives as another voice reifying a socially constructed collective memory. That is to say the archives both shape and are shaped by a much broader conversation about American history.

It is for this reason that I remind readers again that these letters cannot tell us the full story of WWII, of the WASP, or even Margaret and John. Readers may, therefore, want to consider these letters as a small piece of a portrait of Margaret E. McCormick, one that captures fragmentary moments of her life: snapshots rather than a panorama. That the woman behind the letters remains largely unknown to us only makes this collection more important because they record an impression, however limited, of a woman who served her country well during a formative chapter of its history.

Works Cited

Lee, Jamie Ann. “A Queer/ed Archival Methodology: Archival Bodies as Nomadic Subjects.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i2.26

Schwartz, Joan M. and Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” Archival Science, vol. 2, no. 1, 2002, pp. 1-19.