Caro Brown: Pulitzer Prize Winning Reporter

Bethany Weston

In curating this collection and approaching the materials in TWU’s Special Collections, I centered my approach around the methodology and rationale presented in Michelle Schwartz and Constance Crompton’s article “Remaking History.” Schwartz, a research fellow at Ryerson University, and Crompton, an assistant professor at the University of Ottawa, argue that narratives must be rewritten in order to centralize female and lesbian perspectives which have been excluded from the patriarchal archival space in order to “[recognize] the long-term effects of systemic oppression and [refuse] the normalized advantages that systematic oppression offers” (145-46). With this attitude, I approached Caro Brown’s collection while also considering that “[b]eing in control of one’s own history is of real political import” (Schwartz 132). Despite her constant advocacy, Mrs. Brown was not in control of her own history and struggled with societal expectations and gender roles. Furthermore, Brown’s documents speak to the need for “our history [to] more accurately reflect the range of lives we have led” (Schwartz 140). Many articles written about Brown refer to her as a “90-pound housewife” who was, astonishingly, capable of accomplishing complex journalistic tasks. Her life experiences embody the tension that emerges when female bodies insert themselves into prominently masculine spaces. Throughout her career and often risking her safety, Brown was consistently present in spaces where, according to society, she did not belong. Curating Brown’s collection through the lens of Schwartz and Crompton’s work calls for Brown to be given the archival space and recognition that she deserves.

Born in 1908 in Baber, Texas, Brown did not have a luxurious childhood. As a result, she acquired the mental toughness that drove her ambitions. When she was 15, the family relocated to Beaumont, Texas. She pursued an education at the College of Industrial Arts in Denton, Texas, now known as Texas Woman’s University. Her education focused on journalism, including a brief stint at the university’s paper, The Lasso, but her studies came to a sudden end in 1929. Interestingly, several accounts report that she was expelled from the university for attending an off-campus event (Carroza 185n17). Soon after, she met Jack Brown, a civil engineer, and they moved to Duval County to begin their lives together.

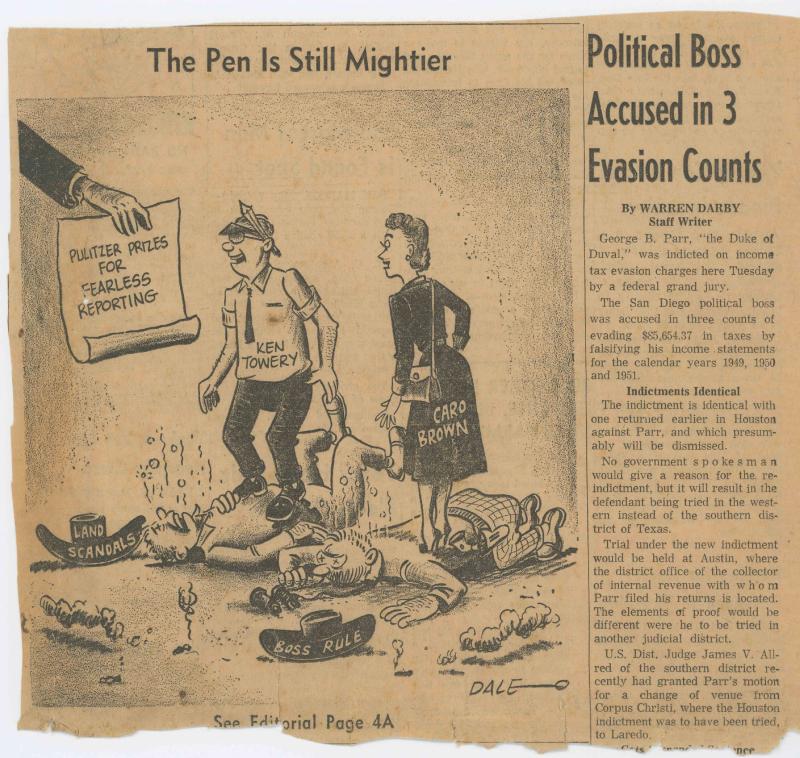

In 1947, after starting a family, feeling distinctly unfulfilled by the role of housewife, and fighting the pressure of societal expectations, Brown joined the staff of the Alice Daily Echo, and proofread articles for $15 a week (Carroza 185). This job eventually expanded into her own column and her role as a courthouse reporter. While Brown was on her upward trajectory, Duval county was wallowing in the dirtiest of political scandals. Working in a “boss” political system, the Parr family had a firm grip on the rural county and its economy (“Caro Brown: Alice Daily Echo”). Reporters on the Parr beat had been threatened with physical violence for attempting to expose the corrupt underbellies of the so-called “Dukes of Duval.” One reporter, Bill Mason, was even murdered as a result of his investigation into the family, and it was at this point that Brown stepped in to cover the tumultuous events (Lynch 60).

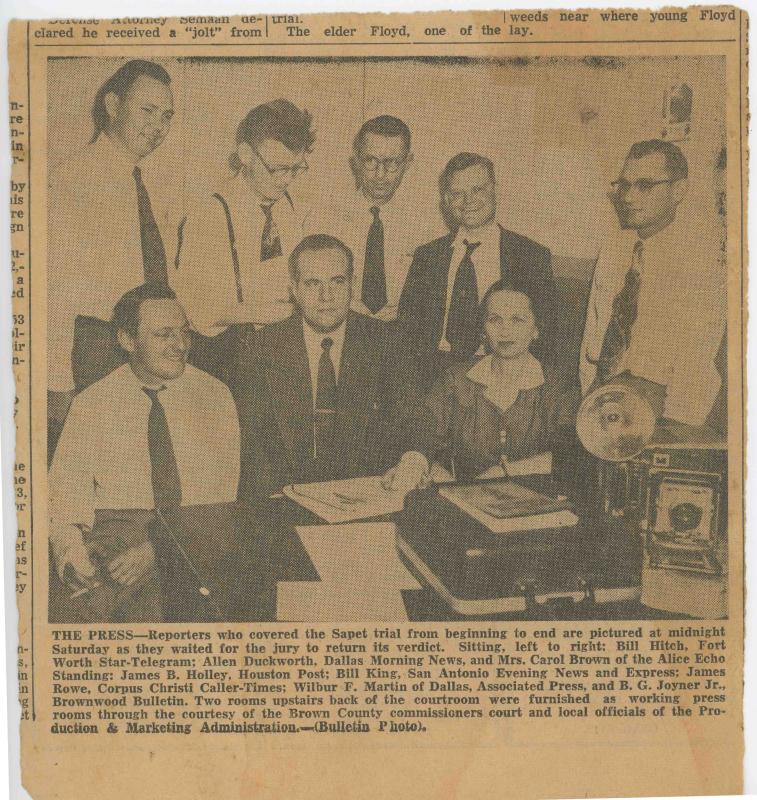

For the next two years, Brown documented her ruthless pursuit of Parr as well as the relentless stonewalling she encountered time and again. Local politicians and government agencies frequently denied her requests for public records and documents, and she took to carrying a pistol, stashing it in the glove compartment of her car, due to violent threats (“Caro Brown: Alice Daily Echo”). One of the photographs contained within this collection shows Brown seated with the other reporters who covered the events in Duval County; she is the only female reporter in the room, attesting to her frequent presence in male spaces and the absolute determination with which she carried herself. While Brown’s stellar reporting earned her the only Pulitzer Prize to be won by a female reporter in the state of Texas, Parr managed to wriggle free of the legal scrutiny brought about by the local court system. However, Brown’s reporting called enough attention to the corruption in Duval county that it catalyzed an eventual and effectual breakdown of the political system (Associated Press).

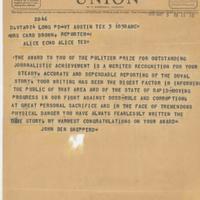

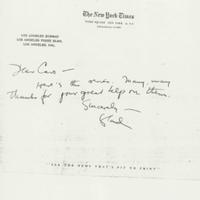

In spite of her journalistic prowess, recognized by many prominent individuals through professional correspondence, Brown continued to feel stifled by societal expectations and traditional gender roles until the end of her life. For example, the telegram from Attorney General John Shepperd which is featured in this collection praises Brown for her “personal sacrifice” and the way she faced “tremendous danger” as a result of her work. The neutral tone of this correspondence contrasts with the many newspaper and magazine articles about her where she was often referred to as a “90-pound housewife” rather than being recognized for her professional achievements. Even after she received the Pulitzer, the Daily Echo would not increase her pay (Carrozza 186).

Brown was a pioneer for local women in journalism, fighting to upend societal structures that encouraged political corruption and discrimination. For her efforts to go unrecognized, in an archival context, is unacceptable. This subcollection is a pathway for continued recognition of her journalistic talents and fearless advocacy for fair political systems. Involvement with the materials in this collection should spark intrigue as well as a desire to understand the forces at odds in Brown’s life: the social and familial, the public and private. Though Brown may have begun as a small town reporter, in a seemingly no-name Texas county, she climbed to national recognition. To the small-town activist, aspiring writer, and everyday woman, she is nothing short of inspirational.

Works Cited

Associated Press. “Caro Crawford Brown -- Reporter, 93.” New York Times, 9 August 2001.

“Caro Brown: Alice Daily Echo.” The Texas Newspaper Hall of Fame, http://newspaperhalloffame.org/index.php/the-inductees/honoress-by-name/caro-brown. Accessed 3 April 2019.

Carrozza, Anthony. The Dukes of Duval County: The Parr Family and Texas Politics. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2017.

Lynch, Dudley. The Duke of Duval: The Live & Times of George B. Parr. Waco, Texian Press, 1976.

Schwartz, Michelle and Constance Crompton. “Remaking History: Lesbian Feminist Historical Methods in the Digital Humanities.” Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and Digital Humanities, edited by Elizabeth Losh and Jacqueline Wernimont, University of Minnesota Press, 2019, pp. 131-56.