Reflection by Daniel Stefanelli

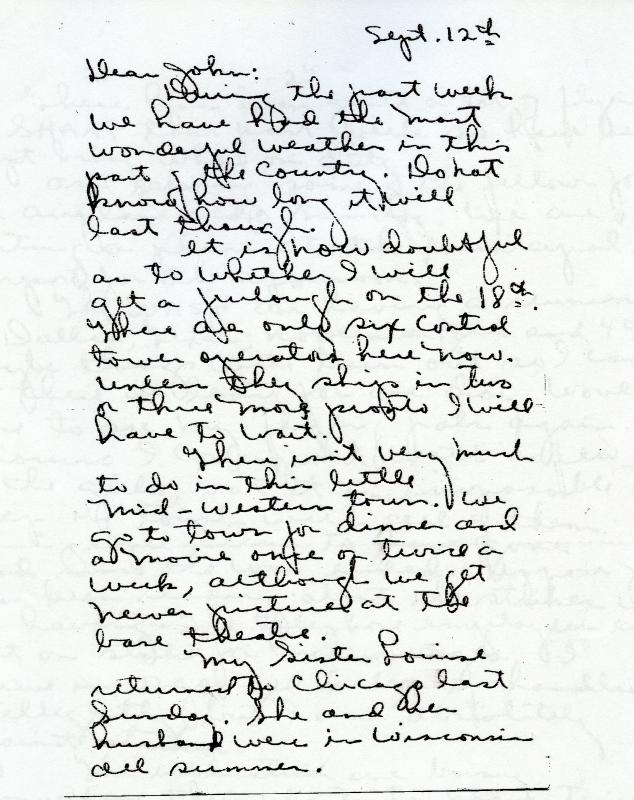

Reading Margaret E. McCormick's letters revealed to me many of her admirable traits: her courage, her tenacity, and her ready sense of adventure. Penmanship, however, was not among her strengths. By far the most time-consuming part of this project, for me, was transcribing Margaret's handwriting. Though generally legible, I would sometimes come across words, lines, or even an entire paragraph that I could not decipher. When I reached those places—gaps, I found myself calling them—the only way I could make sense of them was by reading and rereading the passages around them. Placed in context, the illegible characters suddenly seemed to transfigure themselves into meaningful words.

The video I’ve included here brought that realization home to me more than anything else. In it, a narrator describes the WASP training program for what is obviously intended to be a male audience. To today’s sensibilities, the commentary is absurdly sexist. Within the first minute, the video shows the trainees exercising on the dusty plains of Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas while the narrator explains that the Air Force “wants to get a little muscle on those pretty arms” even before they “get a chance to take the polish off their nails.” I showed this video to several of my classmates, and we all shrieked and laughed incredulously at the overt misogyny throughout the clip.

But, incredible as it seems to us now the video may actually have been fairly progressive for its time with a few interludes reminiscent of today’s feminist discourse. For example, about four minutes into the video we watch a pilot bring a plane safely into the landing strip while the narrator says, “Nobody should ever tell a WASP that flying’s not a woman’s job. They wouldn’t believe it, any more than if it were said a girl can’t be a good flyer and a woman at the same time.”

As much as I may want to privilege the historical moment in understanding this collection––and encourage my readers to do the same—the fact remains that the moment cannot be recreated. Even if I had experienced WWII firsthand, had known Margaret personally or had access to someone who did, the fact remains that the letters are not themselves empirical, objective recreations of the past. At best they are echoes, transformed by the time they reach us by the temporal distance between their moment of inscription and our present moment of reception.

Viewing the letters in this light made me realize that in my eagerness to historicize the letters I had neglected the importance of the collection’s contemporary context: their presence in an archival collection, and their role as a tool in (re)creating a particular historical moment. Fully exploring the implications of this argument is well beyond the scope of this particular blog post, but I’ll conclude by (badly) paraphrasing Dr. Phyllis Thompson’s remarks at the 44th Annual Meeting of the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies earlier this semester. In describing her work in the archives, Dr. Thompson alluded to the role archives have in reshaping our relationships with the materials they house, arguing that ephemera and personal effects become “elevated” by their presence in the archive.

I think a similar dynamic is at play in my interpretation of Margaret’s letters. It’s unlikely that she ever imagined the letters she dashed off after long days of training in the Texas heat would find their way into a library. It’s doubtful that she thought of herself as a person whose correspondence was particularly worthy of archiving, let alone as some sort of proto-feminist icon or voice of her generation. While I have tried not to make Margaret into any of those things, and have tried, whenever possible, to make decisions based on my understanding of the letters’ historical context, this project has forced me to take to heart something I’ve always believed in the abstract: meaning is always mediated and contingent. Our attempts at curation—itself a kind of interpretation—actively shape and reshape the meanings of the materials we seek to preserve.

Works Cited

Thompson, Phyllis. "Scribbled Recipes, Tattered Pages, and Absent Affections: Bearing Witness and the Stuff of the Archives." The Eighteenth Century in Perspective, 23 Feb. 2019, Magnolia Hotel, Dallas, TX. Keynote Address.

"WASPS - Women Airforce Service Pilots WWII." YouTube, uploaded by Buyout Footage Historic Film Archive, 22 May 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gKjShmZCUqc. Accessed 11 April 2019.